Roadmaps for Increased Agility

Sometime last year there was a Twitter discussion about whether roadmaps discourage agility by committing the team too far out.

I was a bit surprised by this as the people commenting all know their agile development stuff, but my experience with roadmaps was very different; I consider them an essential part of our ability to respond to change. After a bit of digging I realised that most of the contributors to the ‘discourage’ argument thought of roadmaps as long-term feature backlogs. In that context, I don’t particularly disagree with their arguments but this is a very long way from what I think of as a roadmap.

People who write about product management, such as Melissa Perri and Rich Mironov, have long advocated roadmaps that express intent rather than list features to be delivered. When I started delivering a regular roadmap update for Singletrack in 2015 I took a lot inspiration from them and thought a lot about the following questions:

-

What is a roadmap?

-

Who is it for?

-

What does it achieve?

-

How to communicate it?

What is a Roadmap?

A roadmap is simply something that tells people about your future intentions. “Intention” is the key word here, you’re not committing to anything but you are giving some direction. You’re saying “if what we know to be true today doesn’t change, this is roughly what we will do”. Of course, you know things will change but not what, how or when, nor what the impact on your intentions will be.

In practice, intention is limited by both time and detail. It’s impossible to talk about stuff beyond the horizon you can see. For startups this might be as little as three months whereas larger companies may look out two to three years. It was during the transition from startup to scale-up when we started formally publishing a roadmap, and I always felt 12–18 months was a comfortable horizon for us.

It’s also impossible to talk about anything in detail if you don’t yet have (or have confidence in) that detail. Hence our roadmap was necessarily light on detail but nevertheless clear on intention.

A good example of this was when we signalled the intent to support an area of our customers’ businesses that wouldn’t normally make much use of our system. The commercial reasons for this — more users for us and a greater RoI for our customers — were clear but what we would deliver to them really wasn’t. The customer response to this signal was initially ‘faintly positive’ but over the next 12 months we had some very useful conversations with customers and prospects about it and eventually identified a small group of customers we could deliver something valuable to. We worked closely with those customers and delivered something that worked for them, then started to develop that out further as more customers and prospects became interested.

So a Roadmap is something that looks ahead further than your immediate work, out to a point you feel you have some reasonable visibility of, that signals intent — rather than commitment — for what you’re going to do, and leaves the detail to the right time to figure the detail out. That something might be a sheet of paper on the wall, a document, some slides, a series of conversations with each of the interested parties, or possibly a combination of all of these.

Who is a Roadmap for?

A Roadmap is for anyone invested in the future of your development. If you’re a company that raises money then your investors will want to know what you’re going to be working on as they balance the value of their investment in you with your progress against your plans.

But ‘anyone invested’ goes much wider than financial backers to include anyone that commits significant amounts of time or money to you, especially employees. New hires will often ask about current and upcoming challenges during the interview process, the Roadmap is a great internal comms tool at All Hands events to indicate the future direction of the business, and being able to contribute to the Roadmap is seen as a vital bit of engagement regardless of an employee’s role.

Especially in B2B/Enterprise software, customers are invested too. Singletrack charges an annual fee and the replacement of an incumbent system with our SaaS product requires change management, sometimes to a significant degree. No one buys the Singletrack product with the idea they’ll try it out for a couple of months and flip to something else if they don’t like it.

And our prospects are also ‘invested’. Okay, they may not yet be at the point of committing to pay us, but if they do they are not just buying in what the product can do today but also what it will do in the future, especially if they’re looking to sign a long-term deal.

What does a Roadmap achieve?

A Roadmap projects a little bit of certainty on an uncertain world. Of course, nothing is absolutely certain and the global pandemic has showed us that thriving businesses can fail and failing business can thrive when things change dramatically. But there is little we can do to predict or plan for these types of event so there is little point worrying about them, we may as well just focus on the things we can reasonably predict or plan for.

In the example of moving into a new area of our customers’ businesses, some of the conversations we had in the 12 months after signalling intent to ‘do something’ indicated that a couple of customers needed to replace their existing systems in the next year or so and, if we could deliver, they’d rather buy from us than any of the other options they currently had. These ‘foundation customers’ gave a lot of input to the UX design of the new features we’d deliver and gave lots of feedback as we worked through the various iterations and then we were able to draw in the wider group of interested customers as we had something more concrete to show to them and get their feedback on.

In this case we were able to generate demand for an item on the Roadmap, simply by including it on the Roadmap.

In another example, about 18 months before a new industry-changing regulation — MiFID II — came into effect, we signalled our intent to build a set of functionality to ensure compliance. The feedback from customers was instant and universal: yes, we need this. We then discussed the impact that would have on the roadmap as it had been previously and again the feedback was emphatic: we don’t care, this is the most important thing. So we immediately made it the highest priority and started work very quickly on outlining the solution, again working closely with key customers to get detailed input and feedback. Most of the work was delivered 6 months ahead of the regulation date and what remained was then delivered in time for all customers to be upgraded to the new version by the end of 2017, ready for the introduction of MiFID II on the 3rd January 2018.

In this case we quickly validated an idea we had for the product and then were able to both raise its priority and change our delivery schedule, to make sure all our customers got everything they needed in advance of the introduction of the regulation. And that early commitment to integrating the regulatory provisions deeply into our product led to our greatest sales growth to that point.

So a Roadmap can help you generate more certainty by communicating intent to the people invested in what you do, which will inevitably generate feedback that you can then work with to make decisions. The above examples were both ‘successes’ in that the intent we signalled resonated well with customers. We’ve also had plenty of times where we’ve put stuff up on the Roadmap to flat silence or negative sentiment (“Why would I use Singletrack to do that?”). But these are successes too, in a different way.

More introspectively, a Roadmap instills a sense of purpose and direction in the business. This can affect hiring decisions, non-technical initiatives (in the MiFID II example above we found ourselves becoming quite expert in the regulation as we worked with customers to outline the solution and were able to offer basic advice on the regulation to some of the more tardy or further removed customers as to what they should do about it), R&D efforts, preparatory infrastructure work, etc.

Roadmaps can also be an effective sales tool. Obviously no-one should buy something solely based on something it doesn’t do that the vendor says is on their Roadmap but visibility of intent can help a prospect weigh up whether you are likely to be a good fit for their likely future business. I also had a great conversation with a customer, before they signed, when they asked me to take them through the previous two years’ Roadmaps. I was able to show them how much of the Roadmap we’d delivered and to talk them through what we hadn’t and why not. This gave them confidence that, whilst not everything on the Roadmap would be delivered in exactly the way they may want, a good chunk of it would likely be delivered in a form that they would get some value from.

How to communicate the Roadmap?

The thread that runs through all of the above is communication. Your Roadmap isn’t just the static artefact(s) that spell out your intent, it is also the process by which you broadcast that intent, gather feedback, refine the intention and, as things firm up, start to turn intention into commitment.

For us, the artefact that underpinned the process was three core slides:

-

Themes. These are the macro pressures we see on our customers or the product at present. Good for validating what we’re generally trying to do and get feedback on any pressures we unaware of.

-

Current Work. A recap of the just-released version is a helpful context- setter and even at the start of a release we can be reasonably confident what we’ll deliver.

-

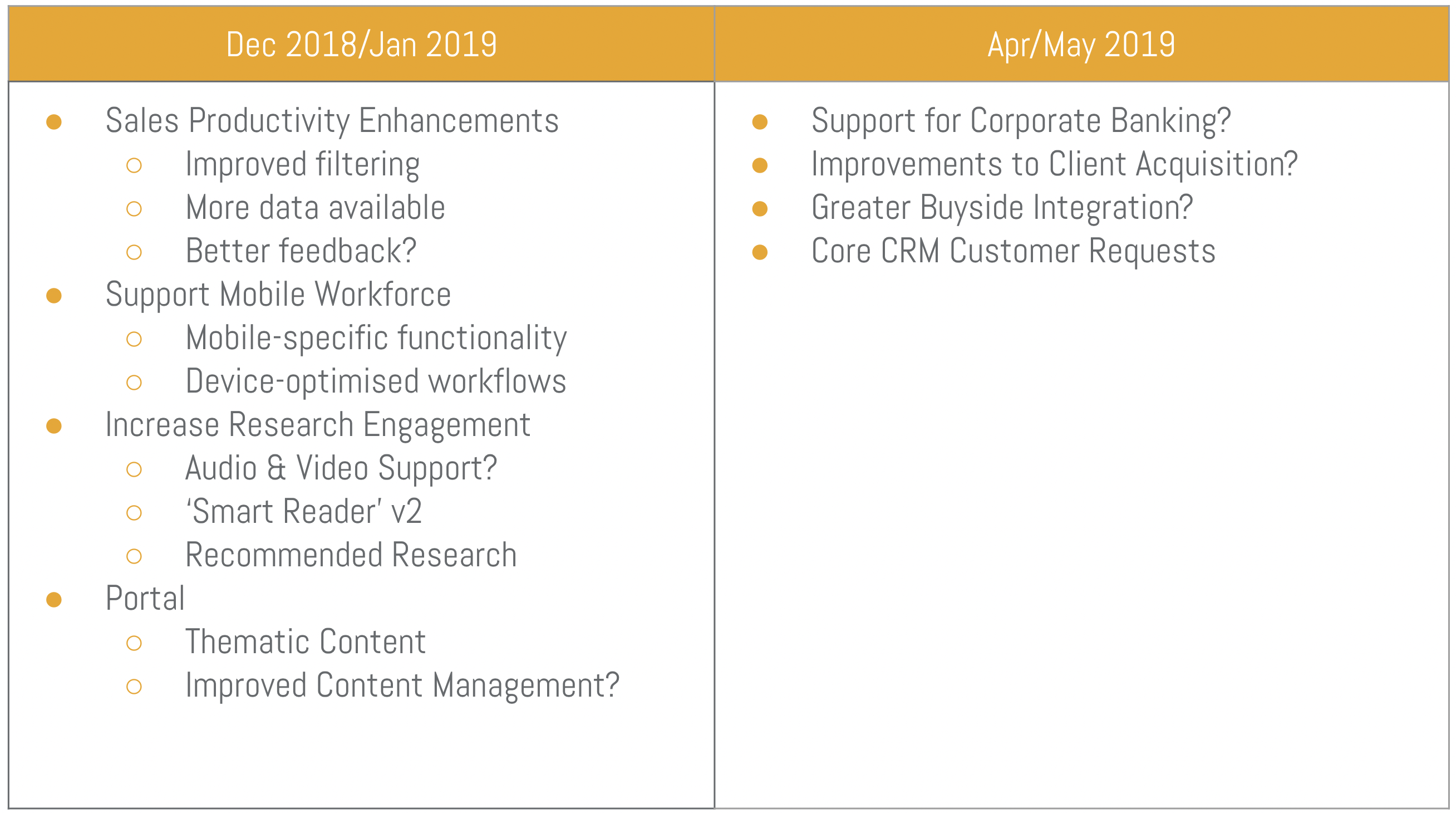

Future Work. The intent for 6–18 months out with less detail and more optionality the further out we look.

Specific presentations of the Roadmap may have more slides, but these were the key ones.

The Roadmap is presented at All Hands meetings at regular intervals and generates lots of useful feedback. Pre-pandemic we ran in-person customer events in London and New York where we presented the Roadmap and took feedback during and after the session. And more recently we’ve been running webinars for all customers and near-term prospects using the interactivity tools to generate immediate feedback. We will do individual walk-throughs of the Roadmap for prospects who are interested and the Roadmap themes are often used in other areas of the business to generate conversation about the things we think that matter with customers, prospects, industry bodies and the industry at large through conferences.

How does a Roadmap improve Agility?

This wasn’t a question I asked myself when we started to turn our Roadmap into a formal thing as it seemed natural to me that it would. But I think it is an interesting question to ask in the face of increased global uncertainty, industry changes in the shift to remote working, etc.

The first thing to recognise is that, if you watched a time-lapse animation of Roadmap evolution at suitable speed, it looks like an agile process:

-

State your intent

-

Gather the feedback the statement generates

-

Use the feedback to refine your intent

-

Go to 1.

In high-stakes poker, the rules of poker remain the same it’s just that the stacks of chips are much bigger. In the Roadmap process, the rate of change for a Roadmap is over weeks and months rather than hours and days but that doesn’t make it any less agile.

The second is that this macro-agility flows ‘down’ to the day-to-day, week-to-week work. In the MiFID II case we knew that, barring some apocalyptic sideswipe, there was nothing that was more important in the next 12 months than delivering the compliance functionality. This allowed us to commit more fully in terms of time and effort spent on this work than we would on something more speculative and, consequently, the team organised itself around the work quite differently than for a ‘normal’ release. And we also varied the delivery schedule from our usual to allow customers to get their hands on all the critical core functionality well before the regulation came into effect, given them much needed certainty and allowing them to train users and set everything up well in advance of the deadline.

In the new business area example, we didn’t think about the delivery work until we had generated a clear demand, using that prolonged period of conversation with customers to focus exclusively on more clearly-valuable work.

Working on things of clear value, close to the point they become valuable, is a key input to an agile development team, allowing them to then iterate around the delivery work, getting feedback as they go, knowing that they’re working on the most important stuff, but still able to change direction if that changes.

The macro-agility of the Roadmap and process also flows ‘up’ to the senior management of the business. The Roadmap has to be informed by, and support the aims of, the business. Hence it becomes something shared by ‘the board’ and the development team, being clear about what we’re trying to do with the understanding that things may well change.